BUYING BIKES BASED ON GEOMETRY

New bike day is coming. You’ve been saving your pennies and doing your homework. After many late nights of research and going to bed far too late, you’ve finally figured out which bike is for you. At last you’re ready to drop the cash. The bike you’ve chosen has the best suspension, drivetrain and components, given your budget, so you know you’re getting the best deal. Sound familiar?

But, consider this. How would you buy a bike if you could only decide on which bike, based on one factor. What “thing” would you choose to differentiate between all the different brands and models? Would it be suspension? Groupset? Wheels? Frame material? Figuring this out will ultimately help you filter through and prioritize which information is more important, when it comes to dropping the cash.

ZEP’s?Mythbuster series has always focused on common flaws in riding technique and offered solutions on how to address these, based on our twenty years of coaching and training instructors. With all the changes in wheel sizing and geometry in recents years, we figured an article addressing how riders should go about purchasing bikes, might help address many of the questions and problems we’re currently seeing.

To do this, let’s first look at how most people currently buy bikes. This is typically based off the information from each manufacturers website and the usual trend is something like this:

OVERVIEW: What the bike is, who’s it for, why it’s rad and what other people have to say about it.

FEATURES: What makes the bike unique… funky axles, unique pivot points, two water bottle cages, some new space-age carbon, and so on.

TECH SPECS: This typically is some kind of list, detailing the fork, shock, drivetrain, brakes, wheels and components.

Trek’s website has the standard Overview/Features/Specs breakdown, with the geometry numbers (like most other websites) at the bottom of the page.

This presentation of information often makes people too focused on things like bike weight, suspension and components, when it comes to making their retail decisions. It makes sense, after all. The advancements in suspension design, 1X drivetrains, dropper posts and wheel sizing have all had significant impacts on improving the way bikes ride today, and it’s fun choosing between all these different things!

This is cool in that customers can make informed decisions… but are they missing something that would help them find a better bike? While choosing bikes based on components or suspension is easy to understand, it shouldn’t be prioritized to the point where we forget about geometry.

Why?

- YOU CAN UPGRADE OR CHANGE MOST COMPONENTS. Either through parts wearing out or being damaged, or simply through personal preferences, most components can be swapped out at some point. Assuming you keep your bike for a few years, like most people, choosing the bike based on what components or suspension it has, while useful, these shouldn’t be the only things to consider.

- FOR THE MOST PART, EVERYONE MAKES REALLY GOOD GEAR THESE DAYS! I’m sure there’s people out there that will swear to never ride brand X or use brand Y, and I certainly have my favourites. But in the big picture,?within each price point, most drivetrains, suspension, brakes, or wheels all perform quite similarly. While it’s a great time to be a mountain biker, this also means prioritizing purchasing decisions based on parts and component lists, makes less sense.

For example, take a look at these two bikes.

Both of these bikes are 2018 Enduro 29ers. One carbon, one aluminium, both similar price points and both with top level kit. However, the difference in how these bikes ride has more to do with their geometry numbers, than their component specs.

You can have all the best components in the world, but if the bottom bracket (BB) is higher and the head tube angle (HTA) is steeper, the bike will corner at speed worse and have less stability, than a bike with a lower BB and slacker HTA.

If you already purchase bikes using geometry as a key decision tool, then great. But if not, hopefully this will make you reconsider how you choose what bikes to ride, and give you some pointers to start thinking about geometry without getting too confused or lost in endless spreadsheets!

Of course suspension design also plays a big role in how one bike?performs, compared to another. However, while different designs can deliver different ride characteristics, there are far fewer “bad” designs these days. The fact that most popular suspension designs can be grouped into a variation of one of three designs (single pivot, four bar linkage, high single pivot idler) suggests that there are still many other ways for bikes to differ… and of course, the geometry of the frames these suspension systems are bolted on to, is a huge part of the equation.

Suspension is also relatively adjustable, allowing a rider to tailor that part of the bike to their preferences. On the other hand, what about geometry? Except for the odd bike that has one or two basic geometry adjustments, it’s not something you can change once you’ve bought the bike.

Here’s an interesting question. What would you prefer to ride, a 2002 frame with 2018 components, or a 2018 frame with 2002 components?

A ride back in 2015 with my buddy, Andy, clearly demonstrated the importance of geometry. Andy has a gamut of bikes in his shed ranging from the latest Canyon Strive, to this old Giant, below. He loves bikes and is incredibly good at riding them (he’s been known to keep up with various pro’s in Whistler Bike Park, once upon a time).

You could argue that, really, these bikes aren’t that different but from a geometry standpoint, my Patrol was way longer, lower and slacker. While Andy admits his old Giant still feels rad, it’s the steep head tube angle (HTA), short wheel base and high bottom bracket (BB) that limits the bike, more so than it’s old (but still functional) components.

To put it simply, build kits, components and suspension are of course going to change how a bike rides. All we’re saying is, be aware of how much emphasis you put on these things when compared to geometry, the next time you choose a bike.

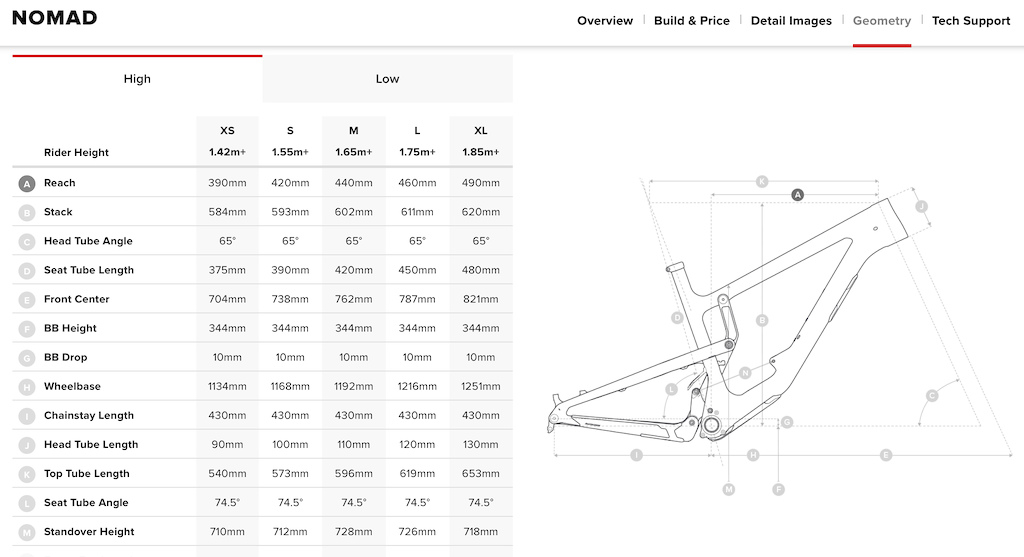

But where do we start? What is “good geometry”? What geometry makes a bike climb better or corner better? How do all those numbers translate to how a bike fits, feels and rides on dirt? I know, it can definitely seem confusing when you see geometry tables, but ones like this from?Santa Cruz?make it easier with a diagram as well.

As I’m sure you can guess, bike geometry can get really complicated. Unfortunately, this is why companies often focus on “specs” and “features” to sell bikes, rather than the information that really matters. Plus, geometry is also kind of a hard “sell”… it’s not exactly exciting stuff, is it?!

The key here then is to try and make geometry easier for us to understand, so we can buy a bike simply by looking at a few numbers on a spreadsheet. I know that sounds weird, but you can actually do this!

However, geometry is a huge topic. It’s hard to talk about one thing without talking about everything. But in the interest of simply getting you guys started, we’re going to focus on just four geometry numbers: reach, head tube angle, seat tube angle and fork offset. Things like front and rear centres also have a huge affect on how a bike rides, but if we delve into all of it, we’re going to fall too deep down the rabbit hole.

And remember, the goal here is to simply have a little more info to help us buy better bikes… not to be an expert in geometry!

USER FRIENDLY GEOMETRY EXPLANATIONS

Reach:?As the name suggests, this is basically how long the bike feels. It is typically measured in a horizontal line from the bottom bracket, to the middle of the top of the headtube.

A longer reach typically results in a longer wheelbase (assuming all other dimensions are similar), making the bike feel more stable, while giving the rider more “room in the cockpit”. This gives a feeling that the rider can move more on the bike, before they start to feel unstable. A reach that is too long can be uncomfortable, especially when seated, and can make the rider too front heavy. A reach that is too short, makes the rider feel cramped making it harder to climb and the bike less stable, overall.

Typical reach dimensions are outlined in the table, below.

Head Tube Angle:?In simple terms, this describes how much the fork rakes out, away from the frame (slack) or is “straight down”, keeping the wheel tucked under the frame (steep).

Slacker HTA’s make the bike better at descending, more stable cornering at speed, but potentially less precise steering at slow speeds. Trail or Enduro bikes with slacker HTA’s therefore often have shorter stems to balance this out to maintain steering precision. Conversely, cross country bikes with steeper HTA’s can adopt longer stems.

- 63 – 64 is typical for downhill bikes

- 65 – 66 is typical for enduro bikes

- 66 – 67 is typical for trail bikes

- 67 – 69 is typical cross country bikes

Seat Tube Angle:?This basically dictates whether the seat is more directly over the bottom bracket (steep), or slightly behind the bottom bracket (slack)

- 73 – 77 is typical for most bikes.

The steeper it is, the more the riders’ hips are directly over the bottom bracket. This helps deliver power into the pedals, while helping to keep the rider more centred (over the front wheel) when climbing steeps.

Companies have often overlooked this factor in recent times, in favour of a slacker HTA. There’s plenty an enduro, trail or even cross-country bike out there that could climb and pedal so much more efficiently, if the STA was a little steeper. However, if you steepen the STA, you reduce the reach, making the bike feel shorter when seated. Geometry is thus always a balance between different factors to find the sweet spot, for any given bike design.

Enduro bikes are the ultimate geometry puzzle. Getting a bike to genuinely climb like an XC bike and descend like a DH bike, certainly has it’s challenges. photo: Eddie Muscroft www.bikeparkphotos.com

Fork Offset:?This a small, but very important measurement. If you look at the bottom of your fork, you’ll notice the axle of the wheel isn’t directly on the bottom of the fork legs. The axle is actually on the “front” of the fork legs… hence the term “offset”. Fork Offset, is the distance from the middle of the axle, to steering axis and is related to wheel size.

- 52mm is typical for 27.5 downhill bikes

- 46mm is typical for 27.5 wheels

- 51mm is typical for 29 wheels

- ?37mm is reduced fork offset for 27.5 wheels

- 43mm is reduced fork offset for 29 wheels.

This might seem like a minor detail, but fork offset directly impacts the steering qualities and wheelbase of the bike. A shorter offset brings the front wheel closer to the rider, which means the frame can run a slacker HTA and/or longer reach. A shorter offset also makes the steering feel more stable and helps increase front wheel traction, both climbing and descending.

COMBINING THESE FOR THE IDEAL BIKE

The following process is one you can do with any style of bike; cross country, trail, enduro or downhill. I’ve chosen enduro bikes for this article, but the same ideas would apply. If you want an XC bike to climb better, look for one with a steeper STA compared to it’s competitors. If you want a downhill bike to be more stable, look for one with a longer reach (and wheelbase) compared to it’s competitors, and so on.

To get started, make a list of your ideal riding qualities for the type of bike you want to buy. For an Enduro bike, it might look something like this:

- Climbs well on steeps

- Pedals well

- Stable at speed

- Descends like a DH bike

- Corners well with loads of traction

- Fun and playful, yet stable

That’s a tall order. But let’s try to figure this out. First we need a reference point. The main goal here isn’t to tell you what bike to buy. Again, this is just an example of the process you can go through at home, to help you choose your next bike.

First, learn the geometry of your current bike so you have a “baseline” to compare to. Then go out and ride different bikes, making note of each one’s geometry. Your friends bikes, demo bikes or rentals. Ride anything and everything. Get to know what these numbers mean and how they “feel” in the real world. From there you’ll gain a much better sense of how a bike should ride, based on it’s geometry, and therefore be better prepared to know exactly what you really want, next time you’re in the bike shop.

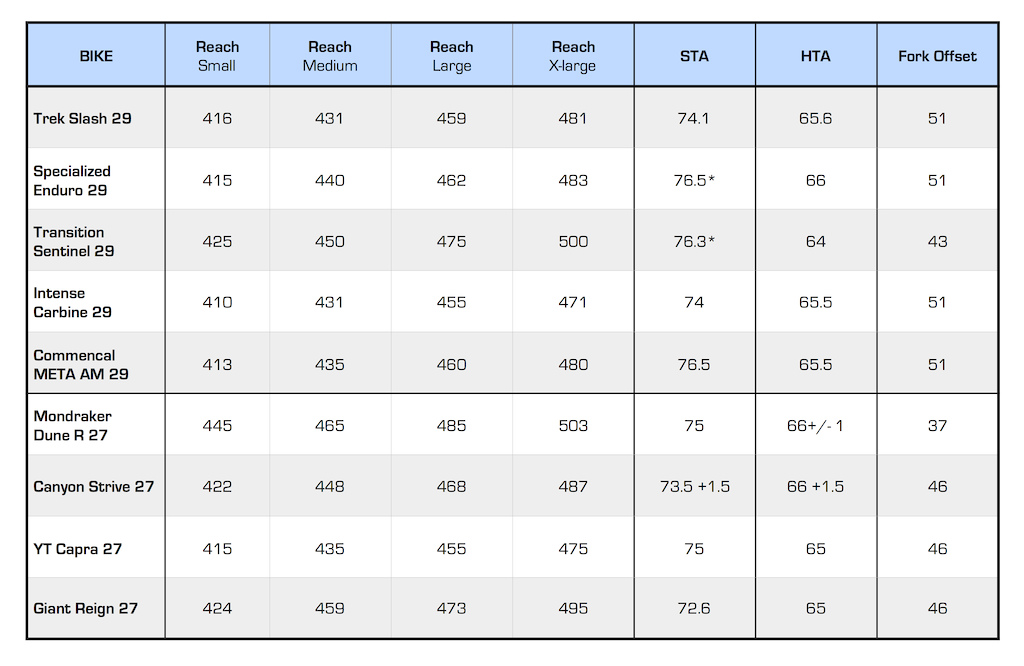

Next, compare these observations (your “collected data”) with a list of bikes you’re interested. Here, we have a list of some of the most popular and current enduro bikes.

Canyon’s bike can adjust it’s geometry to add 1.5 degrees to both the seat and heat tube angles, while the Mondraker can increase or decrease it’s HTA by 1.5 degrees. *Specialized and Transition have different seat tube angles for each size frame, which is awesome, and these figures are for their large frames.

TAKE AWAYS

- SIZING. The first thing to see from this table is sizing. If we look at the reach numbers, you can clearly see that with one brand you could be a medium but with another brand, you could be a large. Indeed, YT actually make an XXL with a reach of 495mm which is similar to the 500mm reach of the Transition Sentinel XL. This is a very common mistake when people buy bikes. They tend to think they are a certain size on one bike, so they’ll get the same size with another bike. No! Check the numbers! People also tend to buy smaller bikes because they are apparently more nimble and manoeuvrable. There is so much more that goes into a bike that makes it playful. My 29er this year is way longer and heavier than my Carbon 27 from last year, and it’s just as fun and playful.

- SLACK SEAT TUBE ANGLES SUCK. This is something you can often feel straight away, in the car park. I’m yet to find a bike with a slack STA that climbs as well as a bike with a steeper STA. This might sound obvious but my point is, it seems the brands with slacker STA’s rarely do anything else with the bike or geometry to counteract it. They simply have a slack STA. Of course though, if climbing steeps or pedalling efficiency isn’t on your list of priorities, then this will be less of a concern.

- SLACK HEAD TUBE ANGLES RULE. If you like the fun side of riding, descending steeps, jumping, railing corners, than a slacker HTA, combined with a longer reach, is going to make the bike way more capable and confidence inspiring. The slack HTA helps the suspension absorb impacts better when compared to a steep HTA.Don’t forget, this is all relative. A slack HTA for a cross country bike would be steep for an enduro bike. But comparing different bikes in the same “class”, will help you figure which one is right for you.

- IT’S ALL TIED TOGETHER. A long reach and slack HTA has it’s limits. That’s why the Commencal and Transition are leading the charge here. With a long, slack bike, this places the rider further away from the front wheel. By steepening the seat tube angle this balances things out and places the rider more in the middle of the bike, helping the bike to climb and pedal better when seated, while still shredding the downhills.

The Transition Sentinel 29er outperforms many lighter, trail bikes on the climbs (there’s some XC World Cup machines with seat tube angles two or more degrees slacker!) and many enduro and downhill bikes (it has a longer wheelbase than many DH bikes), because of it’s unique geometry. That fact that it’s heavier or has different components to other bikes, has little to do with why this bike rides the way it does. photo: Danika Wilson www.bikeparkphotos.com

Mondraker and Transition have taken it a step further. Since realizing that fork offsets haven’t really been experimented with since we were all on 26″ wheels, these brands have worked with the suspension manufactures to offer reduced fork offset as standard, on their production models. The effect this has on the overall geometry (and therefore capabilities) of their bikes cannot be understated enough. This is genuinely a game changer.

Why? The reduced fork offset helps bring the front wheel closer to the rider, allowing them to make the reach longer. Mondraker have the longest reach numbers, because of this. Transition have capitalized on the reduced offset a little more. A longer reach also means they can run a steeper STA, without cramping the rider; so the bike climbs better and has more room to move. When it’s combined with a shorter stem, the reduced fork offset also ensures slow speed steering precision, even with a super slack HTA; meaning it shreds likes a downhill bike but still has the slow speed agility of a trail bike. Changing the fork offset allows many characteristics of the bike to change for the better.

My goal here (and yes, hands up, I am a Transition supported rider) isn’t to sell you on a particular brand (the new?Yeti SB150?looks amazing), but simply to highlight how one geometry number can directly impact how the rest of the bike is designed. The more we understand the big picture and how fork offset, HTA, STA and reach all work together, the better our retail decisions will be.

BUT WHAT ABOUT WEIGHT & WHEEL SIZE?!

After twenty years of coaching, a common issue we still see is people prioritizing weight and pedalling efficiency, a little too much. Their light weight, climb-friendly bike, doesn’t give them the stability or confidence to progress or try new things on both the ups and downs. Along with skinny xc tires (minimal tread), small brake rotors and narrower bars, people aren’t setting themselves up for success… or fun!

People often steer away from bikes with more travel and/or more aggressive geometry, because the say “they don’t need it”. As a result, they often end up with a bike that limits their progression and is too focused on things like pedalling efficiency, rather than learning and having fun!

Try and buy a bike that will support and encourage you to descend faster, corner harder or ride more challenging trails. Flicking through some geometry charts (www.geometrygeeks.bike?is a good website) and you’ll see things like the awesome?Commencal?Enduro bike, actually has a steeper STA angle than certain cross country race bikes. A lighter bike is obviously going to help pedal and climb, but there’s a lot more to how well a bike climbs, than it’s weight. Plenty of trail and enduro bikes out there are actually more efficient for many riders. On technical, rough terrain, light cross country bikes can feel less planted and have less grip, even on climbs, and are more tiring to descend and corner with, since they require so much more skill and finesse from the rider.

Obviously wheel size will also make a big difference to how a bike rides and 29ers do use and need different geometry to 27.5s. A good place to start is to choose a wheel size first, to help simplify the decision making process. Trying to decide between bikes with different wheel sizes and different geometries, will start to get confusing real quick, if you aren’t already!

Since we’re on the subject, we all know the early generation of 29ers kind of sucked. Even when they started getting decent wheels, tires and suspension, they still weren’t great. What makes the latest 29ers so fun and incredible to ride (the 29er Specialized Stumpy I rode for a few days last year, was so fun!) is that the manufacturers have finally dialled in the geometry. It’s the perfect example of geometry ultimately controlling how a bike rides. And they’re not just for tall people anymore! Christina Chappetta just piloted her 29er to a 6th place at the EWS in Whistler and check out 5’2″ Katy Winton’s (currently ranked 3rd in the Enduro World Series) detailed interview on both her 29er and 27.5 Trek race bikes?here.

TO SUMMARIZE

- Try to prioritize geometry numbers over weight or component specs. That’s not to say those things aren’t important, but try not to focus on them exclusively!

- Steeper STA’s are great for pedalling and climbing – around 76 is lovely.

- Slacker HTA’s are more fun and confidence inspiring – around 65 for an Enduro bike.

- Longer reach – creates more room and stability on the bike for climbing and descending.

- A reduced fork offset is a game changer because of how it can affect the design of the rest of the bike (they will be the next “big thing”!)

Well, I hope this helps next time you’re in the money for a new bike or writing to Santa. Over time you can start to look at the other geometry numbers, such as chainstay length, bottom bracket height, front centre or stack height. These all play a crucial role in how a bike fits and rides, just as much as the ones we’ve discussed here, but you have to start somewhere. And a good coach only tells you a little bit each time, rather than everything at once!

Cheers,

Paul